Scope of Institutional Deliveries to Reduce Maternal and Infant Mortality(By Dr. Vaibhavi Shende PARC)

Total Views |

Assessing the Scope of Institutional Deliveries to Reduce Maternal and Infant Mortality to ensure Safe Medical Practices under Trained Supervision

In 2024-25, Maharashtra recorded 1,168 maternal deaths statewide, somewhat more than the 1,131 fatalities reported the previous year. During this period, the district with the most maternal deaths was in Pune, primarily because it serves as a referral centre for complicated, late-stage cases. The percentage of institutional deliveries among Scheduled Tribes (ST) has increased significantly—from 68% in 2015–16 (NFHS-4) to 82.3% in 2019–21 (NFHS-5). According to SRS data, Maharashtra’s Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) declined from 55 per 100,000 live births during 2015–2017 to 33 during 2018–2020. While these figures indicate a positive trend, also show significant disparities remain between tribal and non-tribal regions due to uneven access to quality healthcare. Although maternal deaths are on the decline, the issue remains critical.

Various health indicators highlight the urgent need to strengthen healthcare systems in tribal areas. The Under-Five Mortality Rate (U5MR) among Scheduled Tribes (STs) stands at 50.3%, notably higher than the 41.9% observed across all social groups. Similarly, the Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) for STs is 41.6%, compared to 35.2% for the general population. Additionally, a child born into a tribal family faces a 19% higher risk of death during the neonatal period and a 45% higher risk during the post-neonatal period, compared to children from other social groups. These alarming disparities highlight the pressing need to address the root causes of poor child health outcomes in tribal communities and to implement targeted strategies that effectively meet their specific healthcare needs.

Maharashtra has made significant progress in reducing both Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) and Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in recent years. However, substantial disparities remain, particularly in tribal and rural regions, where IMR continues to be considerably higher than the state average.

Health Infrastructure Gaps: At the national level, as of March 31, 2022, there was a shortage of 9,357 Sub-Centres (SCs), 1,559 Primary Health Centres (PHCs), and 372 Community Health Centres (CHCs) in tribal areas compared to the required numbers. Among the states, Madhya Pradesh (2,265), Rajasthan (1,768), and Maharashtra (1,091) reported the highest shortfalls in Sub-Centres. Maharashtra also ranks third in terms of CHC shortages, with a deficit of 52 Community Health Centres. These figures highlight the urgent need to strengthen healthcare infrastructure in tribal areas to ensure equitable access and improve health outcomes. Therefore, these findings highlight the need to identify the root causes and develop effective

solutions to address maternal and infant mortality.

Maternal mortality across a certain area is a gauge of the reproductive health of the women living there. Anaemia and malnutrition, home birth and unsafe abortion, insufficient maternal deaths audit, and delays in receiving proper care at the facility are the main issues facing maternal care in India. The impact of noncommunicable and nutrition-related disorders on maternal and newborn health continues to be a significant public health issue, with countless lives lost annually. In order to lower maternal, PMR (Perinatal Mortality Rate) and NMR (Neonatal Mortality Rate), skilled birth attendance and efforts to increase institutional deliveries should be intensified. Therefore, it is essential to shed light on the quality-of-care issues faced by one of the most vulnerable groups in the community, in order to reduce infant and maternal mortality rates in underprivileged areas of the state.

Trends of Institutional Delivery in Rural and Urban Areas

The share of India's institutional deliveries increased to 88.6% in 2019-2021 (National Family

Health Survey-5, NFHS-5) from 40.8 % in 2005-06 (NFHS 3).

| Location of Delivery | Rural India | Urban India | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2014 | 2004 | 2014 | |

| Institutional births (public + private) | 34.9 | 80.2 | 74.0 | 90.6 |

| Home-based births | 65.1 | 19.8 | 26.0 | 9.4 |

Table 1: Prevalence of institutional delivery in

India, National Sample Survey, 2004 and 2014

There should be increased public sector investment that had a significant positive impact

on the uptake of institutional delivery care. With the implementation of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM),

the use of institutional delivery services in India nearly doubled, rising from 43% in 2004 to 83% in 2014.

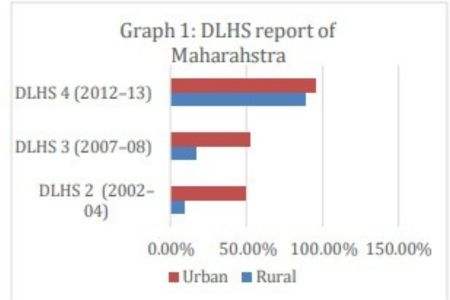

The data on institutional deliveries for Maharashtra at the state level from (District Level Household and Facility Survey)

DLHS-2 (2002–04),

DLHS-3 (2007–08), and

DLHS-4 (2012–13) are presented in Graph

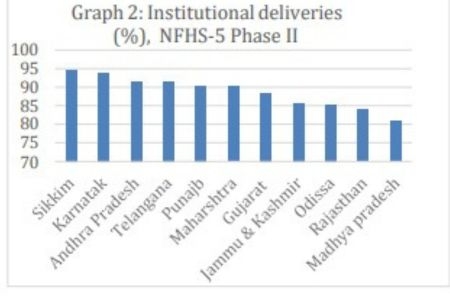

1. According to NFHS5 (Phase 2),

conducted between January 2020 and April 2021,

as shown in graph 2 Maharashtra reported an institutional delivery rate of 90.3%,

ranking 9th among all states. NFHS-4 (2015-16) and NFHS-5 (2019-20 / 2019-21)

report institutional delivery rates of approximately 90% and 95%, respectively.

However, there is a notable lack of updated data after 2021 from government sources beyond this period.

Additionally, some figures may not fully capture ground realities, particularly in rural areas, where underreporting or other factors

might obscure the true situation. The Health Management Information System (HMIS) provides data on the number

of home deliveries attended by non-SBA personnel (such as traditional birth attendants, relatives, etc.)

and the number of institutional deliveries conducted (including Csections) across various districts of Maharashtra.

Quality is never an accident

Quality delivery reducing the burden on quantity

The issue is exacerbated by limitations in human resources. A considerable lack of qualified staff exists, comprising midwives, obstetricians, anaesthetists, and paediatricians. Additionally, numerous healthcare professionals do not have access to ongoing training or continuous medical education (CME) necessary for keeping abreast of current best practices. Due to ineffective supervision and accountability mechanisms, untrained or underqualified birth attendants are often able to perform procedures. Moreover, employees in high-demand environments often suffer from burnout as a result of heavy workloads and lack of adequate staffing.

Institutional delivery needs to be paired with infrastructure, skilled personnel, safe practices, and emergency readiness to be truly effective. Quality must be embedded across the continuum—from antenatal care and facility readiness through intrapartum and postnatal care. This needs structural accountability, performance-based financing, and a motivated workforce.

Postnatal care frequently faces challenges due to significant deficiencies, including insufficient guidance on vital practices such as breastfeeding, family planning, and identifying maternal and neonatal danger signs. Moreover, numerous healthcare facilities— especially those located in rural or overcrowded regions—face difficulties linked to their infrastructure. These issues encompass a lack of beds and delivery rooms, faulty equipment (like fetal monitors, sterilizers, and oxygen cylinders), and subpar transport and referral systems that hinder prompt access to emergency care.

inder prompt access to emergency care. To be fully effective, institutional delivery requires infrastructure, skilled workers, safe practices, and emergency preparedness. Quality must be integrated throughout the continuum, from prenatal care and facility preparation to intrapartum and postoperative care. Decentralized maternal care, nutrition programs, and ASHA worker tracking have reduced maternal deaths. While strong hospital networks support this progress, timely healthcare access for every woman remains crucial. These early interventions and a robust women's hospital network in multiple districts are lowering deaths among women.

The basis for safe birthing is laid by modernizing facilities, making sure FRUs are operational, and setting up specialist maternal care units. Service delivery is improved by following quality standards like IPHS and LaQshya, and gaps in critical care provision are filled via task-shifting and targeted training. By strengthening the link between communities and health systems, empowering frontline staff like ASHAs and ANMs promotes trust and

increases utilization. When taken as a whole, these initiatives create a maternal healthcare system that is inclusive, responsive, and resilient, which can save lives and improve the longterm health of both mothers and babies.

Therefore, assessing the scope of institutional deliveries to reduce maternal and infant mortality underlines the critical importance of ensuring safe medical practices through trained supervision. Also, it is essential to bolster health systems through policy reforms, infrastructure investment, ongoing training of healthcare personnel, and community involvement. Strengthening institutional delivery services and ensuring the availability of trained healthcare personnel in tribal areas is essential to further reduce maternal mortality and bridge the existing healthcare gap. In the end, institutional deliveries should provide more than just access; they must ensure safety, dignity, and quality care for every mother and newborn especially in the tribal areas.